Mandy Heasley recently opened her second cafe, Good Habit, in a former Christchurch convent.

Next month she and her business partners will launch an espresso bar and a large cafe in the city’s new central library, a brave move in an already crowded market.

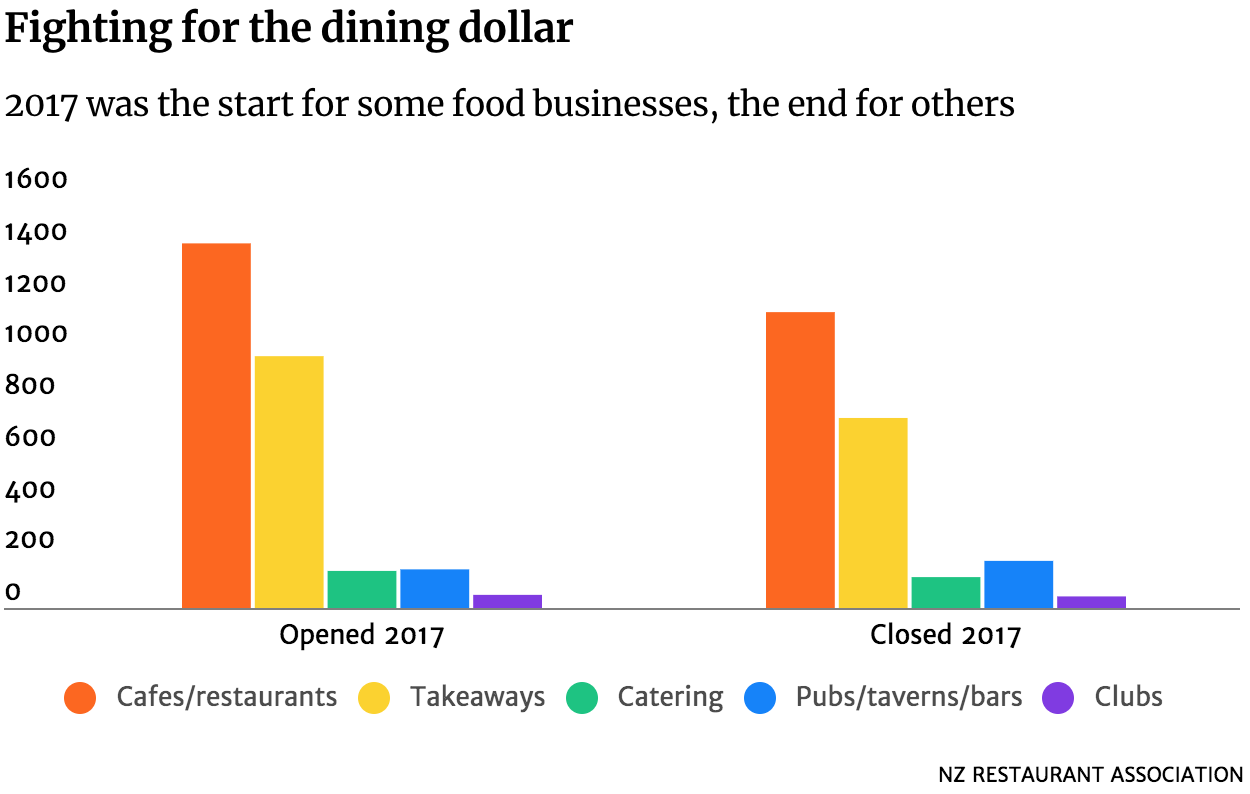

According to the Restaurant Association of New Zealand’s annual state of the industry report, 2739 new hospitality businesses opened last year, the equivalent of seven a day.

There are now more than 17,000 nationwide, with the largest numbers of new premises appearing in Auckland (1200) and Canterbury (339).

Heasley, who has 30 years hospitality experience, says almost every new Christchurch office building in the post-quake city seems to have space for a cafe.

But the library is expected to attract up to 3000 visitors a day, and the historic inner city convent has an attractive garden, so she is confident the ventures will hold their own.

Last year Canterbury got 339 new hospitality outlets, but that hasn’t put Mandy Heasley off opening her third and fourth cafes.

Growth in spending on hospitality has slowed nationally as competition for the diner’s dollar ramps up.

In the year to the end of March, Kiwis spent more than $11 billion at cafes, restaurants, bars, pubs, clubs, takeaway outlets, and on catering services – a rise of 3.6 per cent.

That was well below the 9.7 per cent and 8.5 growth reported over the two previous years.

Restaurant Association chief executive Marisa Bidois sees it as a sign the industry is “stabilising” and she believes continued strong tourism numbers will help bolster any slowing in the New Zealand economy.

“It’s not a huge reduction, it’s just a slight dip and we’re optimistic about the future.”

Bidois says cafes and restaurants continue to be the “rock stars” of the sector, accounting for half of spending.

In terms of total consumer spending, Auckland, Wellington and Christchurch each posted more than $1b in sales annually.

Bay of Plenty performed better than most regions, recording the highest sales growth, as well as the largest percentage rise in the number of businesses.

The Manawatu/Whanganui region was the only one to post a slight decline in sales.

Takeaway outlets experienced the biggest increase (5.7 per cent) with Kiwis forking out an extra $148 million on “to go” food.”

Clubs recorded the only drop in spending and Bidois says pubs, bars, and taverns have had to reinvent themselves with a greater focus on food, because of stricter drink driving laws.

This sector was also the only one where the number of businesses closing out numbered openings, resulting in a net loss of 33 premises.

SUPPLIED Kiwis spent $5.6b in cafes and restaurants last year and a further $2.7b on takeaway food.

Survival of the fittest

Bidois says the average hospitality outlet lasts three years but the Restaurant Association wanted to get a better handle on the rate of “churn” and commissioned Statistics NZ to produce some figures.

They indicate the annual rate of growth in new openings has eased off. Last year, 2739 new businesses opened compared with 2232 closing, leaving a net increase of about 500.

Restructuring, Insolvency and Turnaround Association chair John Fisk says hospitality has always been an easy industry to get into and people lacking business nous can get into trouble, especially if they overspend on the fitout and lack equity to start with.

“It’s quite a fashion industry. Places can be set up quickly and become popular, then for one reason or another, they can decrease in popularity as well.”

In July, well known Christchurch chef Jonny Schwass received six months home detention after misapplying more than $300,000 in tax payments, and Fisk says diverting money due to Inland Revenue is a fast route to trouble.

“Often it’s not paying the PAYE or the GST because they still need to pay for food and liquor supplies, and most businesses are on pretty strict credit terms for that, so IRD can be the easiest target not to pay.”

Events beyond a business owner’s control can hit revenue and Bidois says anecdotally, loss of foot traffic during road works has a significant impact.

When Heasley faced the double whammy of a quiet winter and months of road works cutting access to her Under The Red Veranda cafe, her solution was to sell shares in the business to her chef and manager.

“It was the most challenging time I’ve ever had in hospo. If I hadn’t made some decisions and things had not come right quickly, I wouldn’t have been bankrupt, but I would have had to sell.”

Fleur Caulton owns the recently rebranded Go To Collection with chef Josh Emmett and they are about to about open their ninth restaurant on The Terrace in Christchurch.

Caulton says expanding slowly in the right locations was the key to their stable of Rata, Madam Woo and Hawker & Roll restaurants spread from Auckland to Dunedin.

“We’ve been very focussed on sites and we try not to grow too rapidly …making sure the business is in a good place before we do another one.”

STACY SQUIRES/STUFF More than half the almost 130,000 workers in the hospitality industry are employed in cafes and restaurants, including Gina Bartlett, manager and barrista at Christchurch’s Good Habit cafe.

On the job

Close to 130,000 people work in the hospitality sector with the total number of employees growing by more than 8000 last year.

The Restaurant Association report says lack of skilled staff remains the industry’s biggest challenge and the problem has been compounded by demand from new outlets.

Bidois acknowledges that historically low pay rates have contributed too, but a survey of operators late last year showed just over half intended increasing wages over the next year by an average of 3 per cent.

For wait staff, the average hourly wage was $16.58, while executive chefs enjoyed a 20 per cent increase and now earn $32.14 an hour on average.

Many owners were worried they would not be able to afford the roll-on effect of the proposed increase in the minimum wage and were concerned at the prospect of a Government clamp down on migrant labour.

KEVIN STENT/STUFF Wellington restaurateur Steve Logan says hospitality workers deserve to be paid more, but stiff competition for customers makes it tough to cover increased wage costs.

Steve Logan employs 50 staff across three Wellington establishments, including Logan Brown restaurant, and is heavily reliant on migrant workers.

“I would say maybe a third would be working on holiday visas or a skills shortage visa.

“It’s a low wage industry but it shouldn’t be. It’s a talent to be able to manage customers expectations … dealing with people who might have had a couple of beverages.

“There’s a lot of pressure compared to other industries.

“They deserve to be paid a lot more but there’s a ceiling to how far the selling price [for a meal] can go because there are so many great restaurants around. It’s a real buyers market.”

Unite Union has about 4500 members working in the takeaway sector and national secretary Gerard Hehir says low wages and poor conditions contribute to high turnover, which is ultimately costly for businesses having to train new staff.

“In our union, of a 100 [workers] that start at the beginning of the year, by the end of the year, 66 have gone. That’s a huge drain on productivity.”

Hehir says enforcement of labour law is important to prevent exploitation of workers, and stop good employers being damaged by competitors who underpay their staff.

“If you have someone opening down the way, it can take 30 to 50 per cent of your business, so it’s cut-throat. They might only last a few years before they get caught out or close, but they’ve done a lot of damage in the meantime.”

Migrant workers are vulnerable because they often need supervisory level jobs to get skills visas.

Hehir says these salaried workers can end up working such long hours they earn less than minimum wage. A case in point was the recent action barring the New Zealand owner of Burger King from hiring migrant labour for a year after it underpaid a manager.

JOSEPH JOHNSON/STUFF “Instagram-able” features, like this mural at Original Sin restaurant on The Terrace in Christchurch can provide valuable social media publicity.

Future Food

Bidois says social media and online sales are influencing the way hospitality businesses operate.

New Zealand is beginning to catch onto the overseas trend towards “ghost restaurants” which fill online orders delivered by third parties, with no public store front.

These virtual restaurants have lower overheads because they do not need wait staff and the first one here opened in Auckland a couple of months ago.

The rise of social media has made owners aware of the need to make their establishments “instagram-able,” providing places where people want to be photographed, Bidois says.

“There’s a lot more pressure on fitout than there was 10 years ago because it is so much more visible. In today’s competitive market, anything like that will help.”

The emergence of more meal delivery services, such as Uber Eats and delivereasy, also help restaurants expand their sales.

At Logan’s Cuba St burger restaurant, Grill Meats Beer, online orders make up about 5 per cent of turnover but he believes there will always be demand for fine dining.

“With Uber Eats you’re sitting on the couch and just getting a feed, but if you come to Logan Brown, you’re getting an experience, people are taking care of you and it’s quite special.”

Fit outs costing $1m-plus are not uncommon, especially in the main centres, but Logan says flash interiors won’t make up for other deficiencies.

“You can get away with a rough place if you’ve got great food and great service.

“But the coolest space won’t look any good when the food is foul or the service is rude.”

Hospitality workforce snapshot

- About 50,000 work in Auckland

- Almost 60 per cent of cafe, restaurant and bar staff are female

- More than 40 per cent are under the age of 25

- Nearly 38 per cent work part time

- A takeaway worker makes $102,743 worth of sales annually

- A restaurant and cafe worker makes $76,611 worth of sales annually